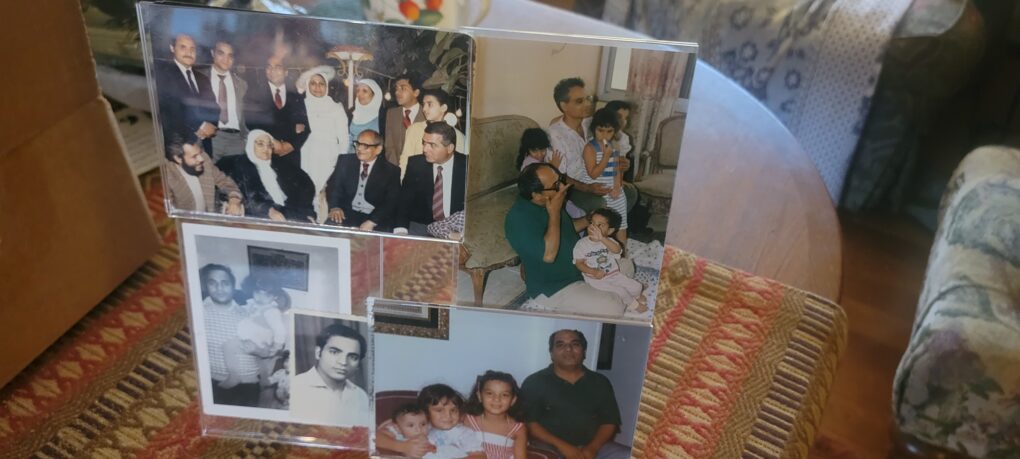

rejected all the offers mad, not enough prestige, not enough money… “You deserve much more” he always said. ” We both going to beg for money on the street Shiekh Obe if we ket this going,” I told him. Growing up, we didn’t have obvious sibling rivalry, it was simple, he beats me in running and wrestling, and I beat him in oratory quibble, in school I advanced much faster. My brother helped anyone he needed help; he lived on a few principles and stuck to them till the end. His religion was not preachy but guided him through his life. Although our family was the educators running the school in the village, As a child, sheikh Obed loved the villagers, and the villagers loved him back. He had difficulties in school but never had problems growing up. Our family moved from the village to Cairo, my brother made the transition much smoother, and the big city didn’t trouble him, he was assured and a confident village boy. In high school he once asked the Arabic teacher to explain the new song for the Egyptian diva Um Kalthoum, Ennta Omery (you are my life), the teacher shamed and shunned him “shut up a village boy”. I protested the harsh insult, the teacher asked me to leave the class. sheikh Obed had problems in the Arabic class, my dad was an Arabic teacher, . During the final, there was a question in an exam that was a tricky one, teachers in Egypt enjoy torturing students. I knew that my brother’s straightforward moral thinking, he is going to get it wrong. I wrote a note and slipped it under the table to alert my brother of the elusive question, he insisted on his answer, it was the right moral one. During a political demonstration, my brother was coming home, he was just 17, police mobs had cornered him, beat him in his own street, when everyone satisfied his savage instinct, the beaten stopped an overzealous soldier, hit my brother one more blow on his head “That one was no ever need for this one” sheikh Obed reflected, he laughs every time someone tells the story.I watched him blossom and become a beautiful man; he was more mature than his age and that was a rarity in Egypt for young boys. sheikh Obed at home seems always fighting to say something, to make his point, with a family of ten, it was crowded. My dad developed a habit of teasing us at the dinner table so someone would leave in protest, making more space, and more food at the table. There wasn’t always enough place or food for everyone. One day my dad slapped my brother at the dinner table, for violating etiquette; eating fast. ” I’m not leaving my spot, I will eat anyway” sheikh Obed fired back, everyone laughed and my dad had to come up with another scheme to make room at the dinner table. In the sixties the family got its first TV, gathering every evening in the living room, close Curtin, dimmed lights, and everyone quiet, my brother always set on the place that was always available, no contest, on the floor. My brother when he watched TV, used what we coined Shiskh Obed TV rating index, his body position reflected how good what on TV. Good Show, sitting straight, leaning on his side, TV is ok, and flat on his back snoring it definitely a lousy TV. Fashion and trends never impressed my brother, he buys things as if they going to last for every, his gifts for me are still fashionable today. Later I left for America, and our relationship grew stronger and deeper. We talked a lot, joked, and shared memories, and on every visit to Egypt, he insisted on joining me wherever I went, on all my adventures. Shopping with him was a day of the price is right; he has an eye for value things. “it is simple, I look at the product, the craft, materials in it, and I give it a price, “. He explained. When he went to Iraq during Saddam’s time, my brother worked for an auditing agency, they assigned him a job to value equipment and furniture in a government company. My brother found a big picture of Saddam that was hung on the wall. “How do we put a price on this,” he asked his boss jokingly. “write priceless” his boss whispered. sheikh Obed quit and left Iraq the next week. My brother got married, the only marriage where every member of the family attended, even my wife and I flew back to Egypt to attend his wedding.sheikh Obed insisted that I see his wife to be before he finalized the wedding. My brother had five children, two girls, and three boys; the last two sons were twins. Al Hassan and Al Hussein were named after the prophet’s grandsons. My brother was full of life; laughs like a child and defend his turf like a man. He lived the moment as his last, and when you met him; he treated you as the only one he cared about. When I went to Egypt to do a TV documentary in my village, with a crew from Public TV “Untold Story” my brother went to the village and prepared the place for us to stay, accompanied us wherever we went, and cooked for us great meals. The Americans as they were called in the village loved “Shiekh Obed” Everybody welcomed Sheikh Obed; he didn’t have close friends, but he was a friend of all family friends. Everyone was fond of sheikh Obed; even my American 96-year-old mother-in-law remembers him and his generosity when she visited Egypt; he insisted on having her and her husband for dinner at his modest apartment. He was the conscious of the family; he held the moral compass and was involved in all major family decisions. He took pride in serving others, even polishing all shoes in the house on a Friday afternoon. sheikh Obed hasn’t changed much; he had the same childish laughs, and told the same jokes vigorously as they were at the first time; he was a good brother, father, and man. My brother throughout his life survived so many accidents, falling off a ladder, rooftop, and a moving train, which resulted in a head injury, and he had a deep cut on the face trying to shave using an old fashion barber shaving raiser, he was 5-year-old. He survived a police beat, illness, drowning, and many challenges, but he didn’t survive what happened on August 14th, 2013. Egypt was on edge; they just had gone through a transforming revolution a few years earlier. My brother’s young son AL Hassan came to him and asked his permission to go and see the protesters in one of the big Squares near his house. Hassan was a 17-year-old young man, a mirror of his father, loves to travel in boy scout groups, inventor making things from throwaway stuff and trash. AL Hassan wanted to see the sit-in at el Middan where thousands of Egyptians protested the military coup and the toppling of elected president Morsi. My brother was worried; he had his brush with the police when he was his son’s age (17 years old); My brother was worried about his son going to elMidan; everyone in the family was. “These are forces of evil, and they up to no good,” he told his son. The son was not versed rounded in Egyptian political ugly reality, and he insisted on going to the Square. “If you are willing to accept the consequences, it is your call,” he told his son. His son went to the Square. That day the encampment was savagely attacked; hundreds of people were killed thousands were arrested; my nephew was caught in the fray; he was taken away and detained, he never came back home. The family feared for his life; the images on T.V. and social media were gruesome; women and children were crushed under heavily armored vehicles; smoke filled the air, and pullets were everywhere. The family worried about their son and if he was even still alive. Months went by without knowing where he was about. Finally found out their son was in Tora Prison on the outskirt of Cairo. The son lived in limbo for years, with no trial or visits. Al Hassan stayed inside the crowded small cell with common criminals, abused tortured, and neglected. His family goes through the hardship of visiting him once a month, six hours for traveling and red tapes, for only 15 minutes visits, they provide him with money, food, and medicine, the prison in Egypt offers only misery. When the Egyptian Ambassador to America Mohamed M. Tawfik, came to visit Minnesota to ask the Egyptian community to support the “New Egypt,” I asked him how we could support a country that imprisoned and killed our family members back home. Not accustomed to challenges,. “these reports are false and imprecise; nobody in prison without a court order,” he mused. The Ambassador was lying, and he knew he was lying. I told him about the 60,000 political prisoners, including my Nephew, I gave him a letter from my Nephews mother pleading for her son’s release. The Ambassador looked at the letter, without reading it, he promised to investigate and come back to me. He never did; he resigned a few months later to pursue a book writing venture. Later they sentenced my Nephew to 15 years in a summary kangaroo trial where the accused never seen his day in court; my Nephew wasn’t even there. My brother never thought his young son deserved any of these, “It is a mistake; he is a child, “what did he do” he always asked. Hassan will be released soon, …, next week, next Ramadan, Next Eid, Next election, next, next. sheikh Obed lived on that hope, but the next never came. My brother’s health deteriorated; he had a stroke, and he was never the same man I know again. My brother spent most of his time glued to the T.V. watching the news, hoping he would hear of his son’s release one day. On a visit to his wife’s village, my brother felt short of breath, they took him to the hospital in critical condition; had minor surgery and went home the next day, I talked to him that morning, he was in a good spirit and looking forward to recovery, a few hours later suddenly his, the wife was praying, she heard a deep sigh, she rushed to see him, he was sitting on the couch, his head falling on his shoulder, his daughter tried a desperate Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation calling doctors, finally, his big heart stopped, and he passed away in his wife’s arms among the people who loved him. They asked where should he be buried, next to his parents in his village where he wished, or in his wife’s village, near the hospital. It was Friday, the holy month of Ramadan, and the villagers who barely know him, wanted him near them so they attend his funeral. They decided on his wife’s village to be buried next to one of his new admired friends. The whole village went to pay respect to a man they had never met, but they all heard that he was a good man, was a human full of humanity and a man full of madness. I tried to visit, and see him in his last hours, I contacted the state department, and they advised me not to go “We cant protect you in Egypt” was their expalniantion. I loved sheikh Obed for his kindness and simplicity; he was my companion. My brother had lived for years in the hope he would see Al Hassan his son free one day, but this hope vanished. The day they buried sheikh Obed, his son Islam had a boy, he named him Al Hassan. R.I.P. sheikh Obed, you are in a better place now, Egypt is like a Wolfe eating its children.

Please sign my MoveOn Let My Nephew Go petition to

Contact or email Ambassador Motaz Zahran

Embassy of Egypt

3521 International Court N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20008

Tel: 1-202-895-5400,