Especially for a young boy in a remote village in Egypt, where the boxer’s battles had parallels.

Donald Trump, reacting last year to President Obama’s assertion that Muslims are among our sports heroes, slammed back: “What sport is he talking about, and who?”

I’m not interested in engaging in a sports contest, especially with a rich white man with bad hair. But my admiration of a black, Muslim sports hero started a long time ago.

As a youngster growing up in a small village in Egypt, I had only two heroes: Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser and boxer Muhammad Ali. Nasser made his fame by championing the fight against Western imperialism and colonialism in the region, spreading Pan-Arab pride. Ali wasn’t just fighting in the ring, but, like Nasser, was fighting American imperialistic expansionism and its ugly war in Vietnam.

As a youngster growing up in a small village in Egypt, I had only two heroes: Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser and boxer Muhammad Ali. Nasser made his fame by championing the fight against Western imperialism and colonialism in the region, spreading Pan-Arab pride. Ali wasn’t just fighting in the ring, but, like Nasser, was fighting American imperialistic expansionism and its ugly war in Vietnam.

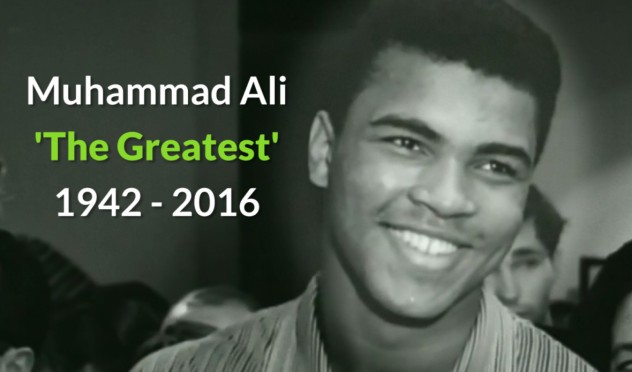

Even before he converted to Islam and bore an Arabic name, Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. captured my imagination after his epic victory over Sonny Liston in the world heavyweight championship match in 1964. He was a fighter whose words were sharper than his fist. “I’m the most recognized and loved man that ever lived cuz there weren’t no satellites when Jesus and Moses were around, so people far away in the villages didn’t know about them,” he once said. And he was right — in my village on the Egyptian delta, there was only radio, and it was magical.

On the occasion of an Ali fight, I would wake early while everyone else was asleep. The birds would be singing outside, and the roosters would be starting their calling routine. There was no Al Jazeera, no CNN, and I had to wait for the morning news, where two items would be dominating: Nasser’s accomplishments and Ali’s winning streak. Somehow we expected the young black man to win every time, no matter the odds. He was fighting our fights; his victories were our victories. My admiration wasn’t because of his Muslim faith, but because of his social justice, his noble stand against the war in Vietnam and his efforts as a young black man winning fights against a racist white system. Ali was a hero for millions of people around the world for one reason or another, and he was winning when it mattered most.

There were other similarities between Nasser the Egyptian hero and Ali the greatest of them all. Both had a great rhetorical skill, but unlike Nasser, Ali fought alone — he talked the talk and walked the walk. (“It’s not bragging if you can back it up,” he once said.) Nasser’s legacy and Pan-Arab inspiration was knocked down in the Six-Day War of 1967, when the Israeli army overran the overrated Egyptian Army and took Sinai, Golan, Gaza and the West Bank.

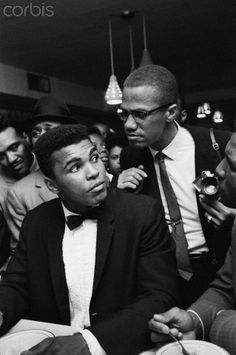

Ali’s real legacy began with his refusal to fight as a soldier in Vietnam that same year and his willingness to give it all up for his principles. Both Nasser and Ali were condemning wars against colored people abroad.

Ali’s real legacy began with his refusal to fight as a soldier in Vietnam that same year and his willingness to give it all up for his principles. Both Nasser and Ali were condemning wars against colored people abroad.

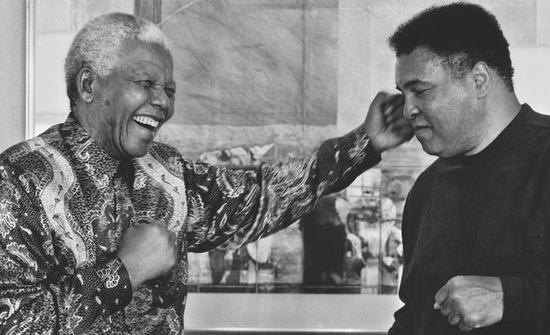

Lots has been said about Ali the boxer — about his speed and talent in the ring — but his political and humanitarian stands outside the ring are what made him the greatest. “Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?” he said, adding superbly: “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong.” He used his fame and celebrity status to shed light on the plight of blacks in America long before Black Lives Matter mattered.

As a youngster living where people would consult with the same fashion designer and pray at the same mosque and play the same game of soccer, I saw, through Coke and Hollywood, the flashy, glassy America. Ali showed me the real America, and the struggle of colored Americans. He was an inspiration for me to connect with America and an assurance that one day, in this strange place, I would always have a friend.

With the irrationality of Islamophobia that’s sweeping the U.S. right now, I always count on Ali’s amazing example of energy and courage, knowing that there are millions of others who share my inspiration from the greatest. Ali was the only fighter to win the heavyweight championship three times. He won 56 fights in his professional career. He then spent more than 30 years fighting the meanest fight of his life, Parkinson’s disease, which hit him in his most talented areas — his physical and linguistic dexterity. May Allah bless his soul and take him to a special place — and I hope it’s a soundproof place, because even in front of God, Ali will always say: “I’m the greatest.”

Ahmed Tharwat is host and producer of the Arab-American TV show “BelAhdan,” which airs at 10:30 p.m. Mondays on TPT. On Twitter @ahmediatv. He blogs at Notes from America at www.ahmediatv.com.

Muhammad Ali, who died Friday, inspired many by using his fame to shed light on the plight of blacks in America.